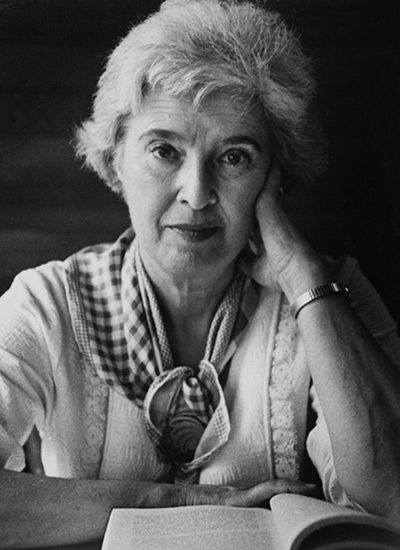

Gerda Lerner (1920-2013)

Gerda Lerner (1920-2013)

Gerda Lerner was the single most influential figure in the development of women’s and gender history since the 1960s. Over 50 years, a field that encompassed a handful of brave and potentially marginal historians became one with thousands; and expanded from Lerner’s development of an MA program at Sarah Lawrence College to the presence of women’s-history faculty in the great majority of US colleges and universities.

She was born Gerda Hedwig Kronstein to a wealthy Jewish family in Vienna in 1920. Her family was typical of the Jewish bourgeoisie in central Europe but also most unconventional, in the way that their class status allowed. (Her autobiography, Fireweed, offers a vivid picture of her family and household.) Her father Robert was an ambitious young army officer who married a woman with a substantial dowry, which he used to establish a profitable pharmacy and pharmaceutical factory. Her mother Ilona soon became a bohemian, an advocate of sexual freedom, vegetarianism and yoga, which “scandalized” Robert’s mother. She became determined to “save” her granddaughters from Ilona’s influence. Since they lived in separate apartments in the same large house, Gerda experienced continual “raging battles” between the two women. Ilona won one battle in naming Gerda’s younger sister Nora, after Ibsen’s play. Ilona was miserable in this house, and it is hard to tell how much due to her mother-in-law and how much with her husband, who was far more rigid and upright than she was. Ilona wanted a divorce but would have lost custody of her children if she had insisted, so she managed instead to talk Robert into a legal contract redefining their relationship: they would continue the appearance of a marriage but would lead separate lives “as long as they were discreet;” and Ilona was granted several months vacation away from home each year. She lived thereafter in a room “marked off from the rest of the apartment. Gerda and Nora had to make appointments to see their mother—the girls were, of course, raised by a string of nannies and governesses. Ilona developed an increasingly bohemian lifestyle, nurturing an interest in avant garde art. She bought a separate studio where she entertained a succession of young boyfriends, while Robert kept a mistress in a separate apartment where he spent most of his evenings.

These familial arrangements gave Gerda early exposure to female independence, along with the entitlements, tastes and unconventionality that the Kronstein class position allowed. She became, she wrote, a naughty girl, misbehaving both at home and at school, even flirting with Catholicism. At age ten she was enrolled in a gymnasium for girls, where she thrived on the academically demanding environment.

As she entered her teenage years she increasingly sided with her mother and began to see her as a “victim of societal restrictions.” Under the influence of some teachers and friends, she was discovering cultural and political radicalism, listening to jazz, and reading modernist literature. She read Tolstoy and Gorky, listened to Louis Armstrong and Bessie Smith, and became a devotée of anti-fascist satirist Karl Kraus.

In 1934 a virtual civil war broke out in Vienna, between Nazis and leftist workers, some of it so close to her home that she could hear the machine-gun fire. At fifteen, she got a boyfriend of whom her father disapproved, which, naturally, ignited her passion for him and for his older brother in absentia, who was fighting fascism in Spain. She began reading and sometimes distributed left newspapers and leaflets. She volunteered for Red Aid, a system of getting help to the families of those arrested and exiled. In the summer of 1936, eager to separate her from dangerous friends, her father sent her to stay with an English family to learn the language; as it happened they turned out to be Moseley supporters and anti-Semites; Gerda got her father’s permission to leave and attend a youth camp run in Wales by the eminent scientist and Communist J B S Haldane, where she soaked up Marxism. (She learned about it by striking up a conversation on a train with a woman reading the Daily Worker.) This was not a timid young girl.

Many Jews began fleeing after the Anschluss of March 1938 and her father joined them after being warned that he would be arrested. He had, presciently, previously established a business in Lichtenstein, which enabled him later to bring his family there. But soon after he left, the Sturmabteilung (SA, the stormtroopers) arrived at the Kronstein house, searching, they said, for subversive books. A month after that, they came with a warrant for his arrest. In his absence they arrested Gerda and her mother, seeking to use them to force her father to return. They were held for six weeks and released only after Robert sold his Austrian assets to Gentiles for a pittance. In prison the two were separated. (Fireweed details the horrors of the incarceration.) Gerda believed she survived only because some Communist cellmates shared their food with her. She also believed that these experiences as a Nazi resister and imprisoned teenager were the most formative influences of her life.

She arrived to the US in 1939, a young radical traveling alone, met by the boyfriend from Vienna, Bernard Jensen, who sponsored her as his fiancée. They married and moved into his circle of German-speaking anti-fascist refugees. In 1940 they divorced, civilly—the marriage had been mainly a means of getting her into the US. She soon met Carl Lerner, a Communist theater director, fell in love, and in 1941 married him. They moved to Los Angeles, where he became a successful film editor. Immersed in the Hollywood Left, she defined herself as a writer on anti-fascist themes. She began to write short stories, one of which was published in a left-wing California literary journal, The Clipper. In 1943, she became a citizen, but not without telling off an INS official who pointed out that she had previously been listed as an enemy alien. (Those who knew her will recognize her prickly, tolerate-no-disrespect style, her instinct to fight.) Having mastered the English language with astonishing rapidity, she collaborated with Carl on some screenplays, including Black Like Me (1964), which he then directed. Their daughter Stephanie was born in 1946, Dan in 1947. She soon became a national leader in the Congress of American Women (CAW), attached to the CP-identified Women’s International Democratic Federation, and was influenced by Communist theorists of male chauvinism, such as Mary Inman. With the CAW she worked with poor black women and began to understand the limitations of her own middle-class assumptions.

McCarthyism hit the Lerners hard. When Carl Lerner’s career was destroyed by the Hollywood blacklists, they returned to New York with their two children. Carl found film-editing work through friends, and Gerda remained active in community struggles, but they left the CP. As for many American progressives, the McCarthyist persecutions were frightening and left a residue of caution among progressives. For Gerda, however, cautiousness did not come easily. Although in the next few decades she hid her Communist past, she remained loyal to her friends and furious at the “friendly” witnesses who denounced others to the House UnAmerican Activities committees, the engines of the McCarthyist hysteria and persecution of dissenters. She continued activism in other spheres. She increasingly turned her attention to women’s groups, such as the Parent Teach Association, and the lessons of Mary Inman took her, twenty years later, into the National Organization for Women (NOW). (Many younger feminists of the women’s liberation movement that emerged several years later thought of the NOW women as liberal, rather than leftist, but this was off the mark: NOW included more blacks, more union women, and more leftists than was then recognized.)

At age 38 Gerda enrolled in college and then graduate school at Columbia, earning both a B.A. and a PhD in six years. Driven by her developing concern with race and women, and defying warnings and belittlement from those who argued for a more conventional and “high status” topic, Gerda wrote a PhD dissertation about the white abolitionist Grimke sisters—children of South Carolina slaveholders, they were the star antislavery activists of their era as well as early women’s-rights advocates. At the time, the only other historian working on the 19th-century women’s-rights movement was Eleanor Flexner, also, not incidentally, a Communist.[i] This affiliation flowed directly from the fact that in the 1930s, 1940s and 1950s, the only political group in the US to raise concerns about sex discrimination—other that the tiny National Woman’s Party–was the CP. Lerner’s choice of dissertation topic was a masterpiece of caution, ambition, and left politics. The US CP had been for several decades committed to challenging racism and recruiting blacks. It was the only white group to defend the Scottsboro “Boys” and its “black nation” program, though foolish, kept racism in focus; in Chicago in the 1930s, for example, 25 percent of its membership was black.[1] By writing about white women who spoke and agitated courageously and eloquently against slavery, Gerda was discussing the racial roots of the American political economy, furthering her goal of organizing women, and producing an innovative piece of work.[2]

With Lerner’s characteristic ambition and chutzpah, she went to a high-status trade publisher, Houghton Mifflin, with her dissertation, and published it only a year after earning a PhD. That achievement also reflected her fine writing style—in her second language.

She devoted the rest of her life to women’s and African American history, bringing to it two aspects of her Marxist education and organizing experience: a relentless focus on power and a grasp of the interrelatedness of its various forms—class, race, and sex. After her book on the Grimkes, her 1969 article, “The Lady and the Mill Girl,” examined class differences among women in the Jacksonian US. Most influential, however, was her 1972 Black Women in White America, a collection of primary sources. African American history was a growing field, but nothing about black women was available. Doubters thought, as they had done about women’s history in general, that a lack of sources made black women’s history impossible. So Lerner’s book was a political act, an eye-opener. It proved that African American women’s history could be written.

Becoming an historian did not disrupt Lerner’s identity as a writer. In 1955 she published a novel focused on Vienna just before the German occupation, No Farewell. She collaborated with her good friend Eve Merriam on a musical, The Singing of Women, produced off-Broadway in 1951. Toward the end of her life, she wrote an autobiography of her early years, Fireweed (2002), which reads like a novel. Writing it was not easy for her, because it required revisiting the horrors of Nazism and her childhood loneliness. But like all of her writing, it is also a history, because she understood all stories, including that of her own life, as shaped by historical structures and events. In writing her autobiography she did meticulous research, aware that memory if fallible (a lesson all historians should take in).

Meanwhile Gerda continued organizing, this time within the academy. In her first job, at Sarah Lawrence College, she quickly recognized that merely teaching women’s history would not be enough to build respect for the field, and she strategized to build women’s history programs with high visibility. Doing this often meant fighting major battles with administrators and faculty members; the battles both rested on and built her toughness and, at times, overbearingness. She began teaching at Sarah Lawrence College in 1968 and worked to establish, with Joan Kelly, an MA program there, which still continues. Twelve years later she won a professorship at the University of Wisconsin, over significant opposition, where she built the country’s first PhD program in women’s history. She loved her Madison community and spent her last years there. She lectured widely on the importance of women’s history, often in an inspirational rather than an academic vein, understanding this work as political organizing.

While she was teaching at Sarah Lawrence, Carl Lerner developed a malignant brain tumor. He died in 1973. After nursing him through this early and miserable death, Gerda wrote a powerful and painfully honest memoir, A Death of One’s Own (1978). It spoke of their relationship, of his right to know the full facts of his illness, of the violence and mystery of death. She never remarried.

Two related intellectual and personal understandings marked Lerner’s career: a visceral grasp of how power worked and a sense of the relatedness of various forms of inequality and oppression—class, race, gender, and global imperialism. It was this astute sense of power that underlay her strategy work to train women’s historians whose numbers and quality would make them non-ignorable. The same understanding also formed the ground of both her scholarship and her advocacy. At Wisconsin she took the job only on the condition that the history department hire a second faculty member in the field, and she brought me there in 1984. I had the privilege of working with her daily for sixteen years and we played bad cop/good cop quite effectively. The visibility of both the Sarah Lawrence and Wisconsin programs attracted top-notch students who were willing to take the risks of earning degrees in a new field, because they were pursuing graduate work not merely as job training but also out of a commitment to movements for social justice. At Wisconsin, for example, the women’s history program required outreach work by PhD students. They organized regular women’s history lectures aimed at a broad public and developed a project for bringing women’s history into the public schools: producing several slide shows with scripts—this was well before the days of Powerpoint—at both high-school and elementary-school levels on women’s work, women in sports, and women’s activism which they then presented in public school classes.

After the Grimke book, Lerner’s teaching and scholarship never again focused on the relatively few elite or successful women who became historically well known. Her 1969 article, “The Lady and the Mill Girl,” examined class differences among women in the Jacksonian US, probably the first such piece within the second wave of women’s historians to do so.

It was her second book, however, the 1972 Black Women in White America, a collection of primary sources, that had the broadest impact at the time. African American history was a rapidly growing field by then, but neither books nor articles focused on black women were available. Doubters thought, as they had done about women in general, that a lack of sources doomed such projects to failure. So Lerner’s book was a political act, an eye-opener, a treasure trove of sources, and a set of clues in the hunt for further sources. It proved that African American women’s history could be written.

Lerner was already a feminist by the 1940s, but in the following decades her political and intellectual orientation grew and changed. Like many of her generation and political background, she was at first uneasy about some of the sexual issues raised by the women’s liberation movement; like Betty Friedan, she worried lest the movement’s provocative style and the coming-out of lesbians stigmatize the cause of women’s equality and women’s history in particular. That changed radically in her master project of the 1980s, published in the two volumes Creation of Patriarchy and Creation of Feminist Consciousness (1986 and 1993). Behind this book lay a new conviction that patriarchy was the first and ultimate source of all oppression.

To do this massive study she left modern American history for anthropology, archeology, mythology and early modern Europe, and read widely in German as well as English-language scholarship. This global study of western civilization was part encylopedism and part Germanic grand theory—using the 19th-century scholars of patriarchy, such as Bachofen, Marx and Engels, against themselves. Through this study she came to argue that control over women’s sexuality and reproductive power was the root of all forms of domination, a radical-feminist rather than Marxist position. Her movement to this analysis probably resulted from in part from frustration at the strength of academic resistance to gendered analyses of violence and domination. Still, throughout the two volumes the two theoretical strands argue with each other. She refuses to accept patriarchy as a biological given, but following the Marxist tradition understands the rise of agriculture as producing patriarchy, albeit a patriarchy varying in different socio-economic milieus; she sees men’s appropriation of women’s labor as evidence that women’s subordination is an economic, not just a cultural matter; and she reminds the reader of class divisions among women. Yet at other times she relies on evidence of female gods as proof of a pre-patriarchal order, and makes a most non-materialist claim that depriving women of education and knowledge of their own history was the root of their subordination.

That last claim, however, was Lerner the activist speaking. She was making the case for the necessity of her life’s greatest work, women’s history, and for it not to be pigeon-holed as a separate “field,” left to specialists. She wanted a holistic history and she wanted a history that served to advance understanding of all forms of injustice.

There was disappointment in her later years: indeed, she had misgivings about the turn to gender history which displaced, she thought, the focus from women and from an active collective subject; and she bemoaned the continued neglect of women in historical scholarship about the largest questions of our past. Gerda’s disappointments were as global as her ambition: growing inequality, religious fundamentalism, the rise of xenophobia and racism throughout the world, American military and security policy. But Gerda was by nature an enthusiast and any uptick in progressive social movements lifted her spirits. She crowed with delight about the “Arab spring” and Occupy. When the massive demonstrations in defense of labor unions erupted in Madison, Wisconsin, in the fall of 2011, she was ecstatic, and had her son Dan take her there, only regretting that she was too frail to be there everyday.

Her enthusiasms were artistic and physical as well as intellectual. She was extremely proud of her sister Nora’s fine paintings and brought an exhibit of them to Madison. She and Nora often met in Europe for spa vacations. Right through her seventies she was a devoted hiker, and her treks ranged from long Saturday outings in Wisconsin’s prairieland to demanding backpacking in the Rocky mountains.

Gerda Lerner won awards far too numerous to mention, including Austria’s highest, the Cross of Honor for Science and Art, in 1996. She is survived by her sister, Nora Kronstein Rosen, an acclaimed artist, of Tel Aviv; her son Dan Lerner, film director, producer and cinematographer, of Los Angeles; her daughter Stephanie Lerner-Lapidus, a psychotherapist, of Durham, North Carolina; and four grandchildren to whom she was intensely devoted.

– Linda Gordon

Linda Gordon was Gerda’s co-director of the women’s history program at the University of Wisconsin until Gerda retired. Today she is the University Professor of History at NYU.

Contributions to honor Gerda Lerner’s legacy and to further the field of women’s history can be made to two funds:

The Lerner-Scott prize of the Organization of American Historians (of which Gerda was president) for the best women’s history dissertation at https://www.oahsecure.org/donate or by mail at http://www.oah.org/donate/pdf/2012oahdonate.pdf

The Lerner fellowship at the University of Wisconsin History Department at http://history.wisc.edu/alumniandfriends/supporting.htm

[1] http://www.isreview.org/issues/01/cp_blacks_1930s.shtml

[2] At the time, the only other historian working on women was Eleanor Flexner, also, not incidentally, a Communist.

[i] Eleanor Flexner, b. 1908, was just old enough to have been part of the “first wave” of feminism, which had produced a small stream of scholarship about women. Some of them, not including Flexner, held college teaching positions starting in the 1920s. By the 1950s, however, there were fewer women teaching at the college level than three decades earlier.